Globally, the youth are not doing well. Addictions, mental health crises and malaise are breaking record upon record in various countries.

At no point in history have the youth felt as alone, as stagnant and as estranged from an expected life as now.

To some this might come to no surprise – complicated issues such as the housing crisis, rising poverty and student debt are chaining the youth to their childhood bedrooms. Some even experience heavy insecurity of more specific things: such as climate change, war or the state of our democracies.

Inevitably it may seem that the youth would rise up and organise efforts to chart a new course for their future: one more secure and pleasant than the one statistically predisposed to them. But their participation in ‘civic-life’, community and politics are reaching all-time lows: a collapse of social capital and the ability to drive change as a worrying consequence.

Why is it bad that they’re not showing up? Who is trying to change this tide, and why does this issue feel so unaddressed? In this article, in collaboration with our partners the Youth Council of West-Frisia and I-DEHA, we create an image of the ever more important fight to give the youth a seat at the table.

THE CHALLENGES OF INTERCOHORT CHANGE

Sociologists consider the changes that happen between generations as ‘intercohort’. For example: older folks who did not grow up with affordable or accessible long-distance calling grew into the habit of writing letters, something the newer generation that did grow up with affordable or accessible long-distance calling never adopted. Each generation, generally, stuck to their own thing. With the ‘great generation’ now mostly passed away, so too did the practice of handwriting letters rapidly disappear.

This phenomenon is represented in voting patterns, hobbies, worldviews and economic decisions as well. A sixteen year old now will make significantly different choices and hold a different worldview than a sixteen year old in 1960, let alone a 79 year old now. Point is, a lot of change happens simply when a newer generation takes the mantle of leaders, tastemakers, members, families, employees and so forth.

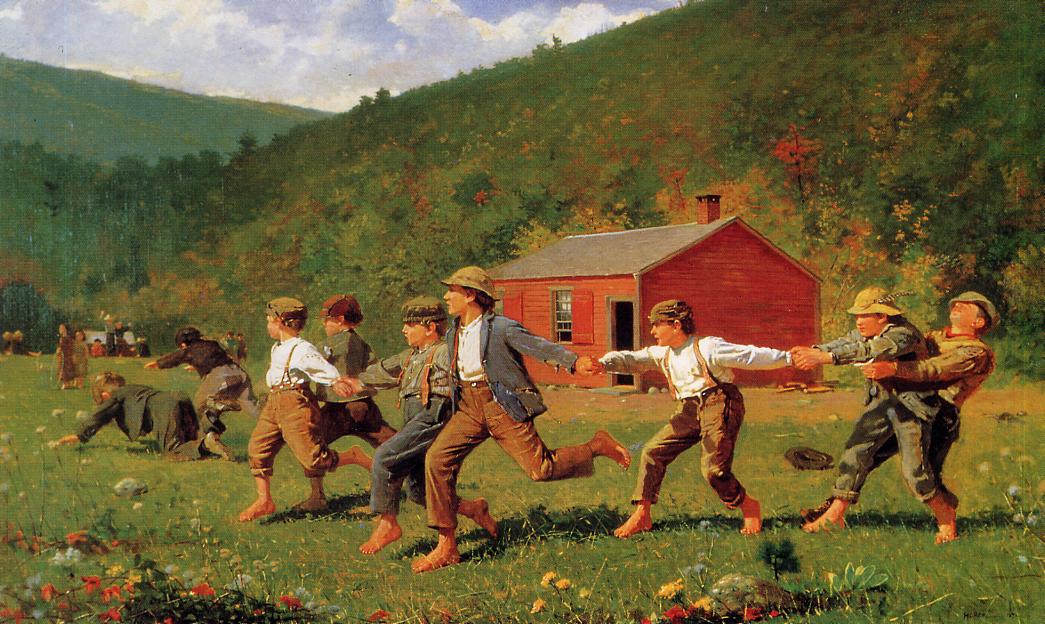

But unlike previous generations, the youth now don’t build local communities. They live on the ruins of now derelict or marginalised neighbourhood committees, interest groups, poker clubs and other forms of social ‘get-together’ groups. Instead, they exist more on a macro scale: finding like-minded people across the globe, and moving their social capital into online platforms. While not inherently wrong, this new allocation of social capital does create a problem: locally, where most of life ‘happens’, much less is built than somewhere far away.

If the youth don’t ‘show up’ anymore locally, who then can become the leaders, tastemakers or members that are supposed to drive change? Their absence creates a norm where institutions, or even society in a more general sense, talk more ‘over them’ than ‘with them’. It becomes stranger if you consider that a lot of organisations in the private- & public sector spend so much energy trying to involve the youth.

TURNING THE TIDE SLOWLY

The Youth Council of West-Frisia, and many Youth Councils across the Netherlands with them, answered the call from these organisations. In their specific case, the many municipalities of West-Frisia found their ‘voice of the youth’ again after decades of trying and wanting to represent it. This Youth Council wasn’t the first by any means. The municipalities carry a long history of failed initiatives and died out groups – making the Youth Council’s success this time only more essential.

The youth council formed a collective power that could lobby and consult the West-Frisian municipalities: giving them a ‘young’ perspective on dossiers such as housing, healthcare or the public domain. The Youth Council didn’t hesitate to initiate their own research with locals, enter dialogue with organisations and push for their own ideas. To the enthusiasm from bystanders in- and out of the system. The youth joining the conversation satisfies something egalitarian and fair across the board.

Like them, Youth Councils have popped up in surrounding municipalities around the Netherlands: claiming their presence in society one proposal and post at a time. They’re creating a new norm where the youth has a consistent presence at the local dossiers that matter: countering the general trend of apathy and underrepresentation. Some, like the Youth Council of West-Frisia, even receive a formal mandate from municipal government(s): granting them a framework to join the conversation and exert influence more directly.

“It is important that the youth are taken seriously by local politics.” Jurre Koopman, Chairman of the Youth Council of West-Frisia, told us “In my own research I found that a lot of youth were interested in societal themes, but not the politics that come with it. We founded the Youth Council to be a place for this large group”. Jurre, together with his many colleagues, are helped by a local figure in education.

Marlina Faber Premselaar, a teacher well acquainted with the sentiment above, viewed the same issue identified by the Youth Council & Plaza, but from a different angle: “Adults and youth alike do not have blind faith in the political system anymore. It is therefore important that this organisation is not staffed by people who already have political careers, or consider this effort as a stepping stone or hobby: but staffed by youth that authentically represent the many walks of life in West-Frisa instead”.

The youth organising outside of the classical party-system de-’politicises’ the issues that they face. This is a positive trend that, at least around and in West-Frisia, is seeing momentum. Though joining the conversation is one thing, defining it is another. These youth organisations are walking into a well-established political, economic & social system that cannot always change even if all parties involved want it to.

THE QUALITY GAP

Governments, local and national, have access to a larger instrumentaria and resources than those that live under them. Municipalities enjoy the expertise of various officials, and wield budgets capable of hiring external expertise from for example consultancy firms. The prices at times reaching the tens of thousands. Any policy, from green management to parking, finds itself extensively developed and researched. Whereas the citizen has neither the human nor financial capital to operate on a similar scale.

This inherently creates an uneven playing field. Whereas adults might find the capital or expertise from careers or connections from the past: the youth are even less likely to have developed either of these at that stage of their life. It becomes a David versus Goliath dynamic: the opinion of youngsters versus a funded and staffed apparatus with its own logic and rules.

Students volunteering to represent the youth do not have tens of thousands euros lying around for a single consultancy report, don’t have decades of work experience in relevant fields nor have the ‘insider’ knowledge of the various dossiers affecting their lives. This situation doesn’t make them less capable or intelligent by any means – just simply less equipped to contribute than who they’re dealing with. The resources of knowledge, manpower & network are not democratically divided.

So even if the youth go against their statistical probability and do decide to participate, they start with a 0-3 score in the system. Not only does this make participation less rewarding, but it affects the immense potential these youth organisations do have. It also makes these youth organisations more dependent on outside help. This can lead to value creation, but this dependency can also be abused. It is difficult to withdraw oneself from the influence of politics when one’s benefactors are at the centre of it.

This is the primary reason why Plaza was eager to hop aboard and assist the Youth Council with various organisational-, administrative- & research-related affairs. To, in a way, equalise the playing field in which these organisations seek to cultivate representation. But to also ensure that it can develop its own voice without interference or compromise. Authentic, but professional. Similar to our involvement with I-DEHA (Turkish education NGO), we hope that these ‘smaller’ bricks will build something greater: organisations that maintain and revitalise the communities we all live in.

Whether they will prove to be a game-changer or just helpful, bringing authentic organisations to communities will revitalise the civic engagement we have been gradually losing, showing people that participation matters. While a youth council in a city might only impact their demographic in that city, it creates new generations of knowledgeable and involved people: who can take the mantle of our new leaders, tastemakers, members, families, employees in our communities.

IF NOT ME, THEN WHO

In Plaza’s previous publication ‘the Turkish struggle with talent’, we identified the issue of lacking infrastructure for interest groups. Infrastructure that would educate the population on the unique struggles of gifted youth: but also the infrastructure to advocate and drive change in society.

In the municipalities that the Youth Council of West-Frisia operates in: the lack of a properly representative and effective youth organisation was the norm instead of the exception for decades. I-DEHA too found itself as a lonely voice in their fight to facilitate the intellectually gifted of Turkey. This happens despite the observation that people almost universally want to represent the youth and want the gifted to pioneer the future.

An important difference to consider is that in previous decades, civil engagement was far more prevalent and ‘normal’. Culturally and socially people would be nurtured into participating in various groups and organisations. One club might have dwindled out of existence early on: but there were ten more boasting memberships enough to ‘move mountains’ in communities. That social capital, in the long term, translated to a better identification and protection of interests. It also protected the community in general from ‘losing touch’ with specific interests: as they all mingled, participated and networked in various strata of local society.

Now if the Youth Council of West-Frisia stops existing there isn’t another avenue for the youth to organise and seek representation. In absence of the neighbourhood committees and hobby clubs, the youth will most likely disappear into the black hole of metropolitan areas. Finding a job, housing and community of their own elsewhere. The youth left behind will not have the same manpower, momentum and network to fill that vacuum locally.

It might be difficult to imagine this in the bustling and urban landscape of the western Netherlands, but this phenomenon is everywhere. From the abandoned villages in Calabria and the university educated diaspora from Turkey, to the dwindling economic power of the rural Netherlands. A stark contrast with the rich civic life of Dutch metropolitan cities such as the Hague, Eindhoven or Amsterdam.

Fighting the uphill battle to create infrastructure for groups in rural areas is not just important, but sometimes the last stand of disadvantaged communities. Especially for the youth, who are supposed to stay and continue the socio-economic activities that keep their cities worth living in.

This makes the mandate of the West-Frisian youth council larger than they think or officially claim to have. Beyond raising awareness and giving consultation on youth-related policies, they are creating an infrastructure to leave behind for the generation after them. An infrastructure capable of adjusting policies, nurturing a subculture and giving youthful talent a place: may find itself able to sway the youth to remain in West-Frisia, and leave the greener pastures for others to explore.